Graham Rawle (1955) is an English author, artist and designer. His latest novel Overland was published in the spring of 2018.

Joonas Säntti: The first thing any new reader is likely to notice about your work is a certain playfulness. There is always a conceptual element or a formal experiment, which often concerns the appearance and traditional uses of the book form.

Your first novel, The Diary of an Amateur Photographer (1998) mixes text with image, uses an envelope as an appendix and the pages look very much like a scrapbook. Woman’s World (2005) is a collage novel composed entirely from cut-out material, the words selected from late 1950’s and early 1960’s women’s magazines and the punctuation marks clipped from novels, using scissors and glue. The spaces between the cut-outs remain clearly visible in the published work. The Card (2012) uses visual illustrations to present the reader with “documents” of the same items that the novel’s protagonist is finding all around him, while also mystifying the reader with changing typography.

Your latest novel Overland (2018) is not one of the easiest page-turners either, because the text is printed “sideways”. This novel, describing an aircraft plant hidden under an artificial suburbia in 1940’s California, has to be read horizontally to find out what happens “over” the ground level (the top page) and “under” it (bottom page).

Are these material and formal elements usually your starting point?

Graham Rawle: No, not at all. I start with the story. It isn’t until much later that the form begins to suggest itself. I’m trying to find the most effective way possible to deliver the narrative so, naturally, the design differs from one book to the next. And it might not even be a book; it could be a film, a play or a piece for radio. If I get it right, form and function should feel intrinsically connected, as if there is no other way the story could be told.

In Woman’s World I used women’s magazines because the protagonist, Norma, a woman obsessed with achieving the impossibly high standards of womanly perfection they prescribe, needs a way to fabricate a female persona. Using the words themselves, with their forthright guidance on womanly wisdom, she finds a voice to tell her subversive story. I had already used some of these collaged text techniques in Diary of an Amateur Photographer, and was excited how the method forced me to become more inventive. I also loved how the words themselves retained the syntax, flavour and moral tone of their original context. I’d been playing with the idea of a completely collaged novel, but it wasn’t until the Woman’s World story that the two ideas began to merge.

In The Card, the first-person narrator, Riley, suffers from apophenia, a tendency to see meaningful connections in unrelated phenomena. In the margins of the text there are coded graphic symbols that act as a kind of notational shorthand for both Riley and the reader, much like footnotes. They help readers to see the world through Riley’s skewed perspective while at the same time saving them from his tedious observations that would otherwise slow down the narrative. In all the books you mention the visual elements aim to carry an additional narrative layer: information is gleaned from the layout, type or illustrative pieces. Often this subtext sits somewhere between image and text, text and text or text and layout, and requires close reading of both for the new information to emerge.

Säntti: I would certainly agree that your novels can be enjoyed as narrative fiction, providing complex and enjoyable storylines, even while commenting on their own nature as artefacts. The immersion and seduction of the reader, the creation of inviting storyworlds seems like an important element. How much do you think about the hypothetical reader (or authorial audience) when you are working?

Rawle: I’m primarily writing books to entertain myself—stories I would want to read, but I’m constantly thinking about how the idea is communicated to the audience. I’m always conscious that I’m asking them to take a more active role, make a little extra effort. Particularly in first-person ‘unreliable narrator’ narratives, much of the story is told through what is not said rather than what is, so I’m essentially leaving narrative gaps that the reader is required to fill. If the story isn’t strong, they won’t be prepared to do this. So, the story is always paramount. If the story doesn’t work, then nothing works and a book like Woman’s World, which took five years to create, becomes nothing more than a gimmicky waste of time.

Säntti: Working on Woman’s World, you chose first to write the text as a regular novel, then look for suitable passages in your collected material, a huge amount of snippets—just how many were there?

Rawle: I think it’s around 40,000 text fragments in the book, but those were taken from a huge collection of gathered material (about a million words) that had to be archived, then transcribed and catalogued so that I could work on the story as a Word document, which went through several edited drafts before I could finally paste the pieces onto the page. There was a system, but it was a complicated and incredibly time-consuming process.

Säntti: This process brings a delicious tension between what you had planned and what is by necessity coincidental, giving birth to some incredible metaphors (“His words had flung open the French windows of my mind and forced me to step out on to the balcony of indiscretion” being perhaps my all-time favorite). Your collage teases out the strangeness of the source vocabulary.

It’s easy to see similarities to constraints used in many 20th century literary experiments. Collage works to liberate the language and opens up strange possibilities.

Rawle: Yes, like the OULIPO authors, I found the constraints of the exercise incredibly enabling. My writing got more imaginative and I came up with similes and metaphors that I would never otherwise have imagined. “Her stare was as cold and as still as a dead man’s bathwater.” Sometimes the narrative took a slight detour to enable me to incorporate a particularly pleasing find. As a result, Norma would suddenly blurt out something silly: “There was a giddy knot in my stomach and my heart was skipping madly to beat of Jack Costanza’s Cha-cha Bongo.”

Säntti: Did having to create a certain individual and continuous “voice” for Norma also mean discarding some of the wildest combinations?

Rawle: Yes, a lot of the best lines got cut or were never used; I had to keep it all in check for the sake of the story.

Säntti: How is your movie project on Woman’s World developing? You premiered a few scenes when giving a talk in Jyväskylä (2017) and I really loved the idea of editing two different films of different times (1940’s and 60’s) into a single frame.

Rawle: The finished film will be assembled from thousands of found footage clips taken from movies, TV shows, advertising and documentaries from the 1940s, ‘50s and 60’s. But you’re right: for the main character, Norma, I have cast Greer Garson, who is primarily a 1940s actress and consequently something of an anachronistic oddity when she appears in the grittier 1962 working-class environment in which the film is set. This will add to the feeling that Norma doesn’t quite fit.

At the moment I’m spending a lot of time arranging funding for the project. I will need a small army of editors and researchers to help me source and assemble all the found material. I can’t wait to get back to it. It’s the ideal project for me: collage, sequence, writing, music—plus I get to trawl thousands of films, both familiar and obscure, from the period I love most. The source material is rich and delicious. Who cares if it takes twenty years?

Säntti: How does your decision to use actual film footage relate to the chosen form of Woman’s World the novel? If working on that was “writing with scissors”, as you have described it, how does editing the film relate to writing?

Rawle: The methodology is incredibly similar; the completed assemblage of archive material will retell the original Woman’s World story, cutting together collage film fragments and layering them both spatially and sequentially. In the same way that in creating the book I discarded my original manuscript and replaced it with the found text, now I will be replacing the book with a found footage approximation of the same story. Extant musical pieces will be deconstructed and refashioned into a new musical score, which will help to gloss over the disjointed visuals. The difficulty of editing together a coherent film from thousands of mismatched shots is obvious, but it’s even harder than I had imagined. Sourced dialogue in print, somebody saying ‘yes’ for example, is essentially stripped of its original inflection once used in a new context: one ‘yes’ is as good as any other. But in film, the original inflection—sarcastic, surprised or sympathetic—is retained, drastically reducing its versatility.

Säntti: Have you found your actor for Roy, Norma’s “brother”?

Rawle: Casting debate for Roy is ongoing. A large part of the decision depends on the depth and range of the actor’s available on-screen performances from which the new scenes will be constructed. More importantly, there has to be a warmth, sensitivity and authenticity that audiences will respond to because, however the pieces are re-edited, these qualities will permeate the new performance. Without them, the audience won’t care about him, and the story will be lost.

Säntti: As a writer and a visual artist you seem especially aware of the relationship between the form and the meaning of a letter, of a word, of a sentence. But on a more abstract level, there is a delightful structural symmetry between narrative technique and subject matter.

Some readers of Woman’s World have suggested that the artificiality of gender becomes very concretely observable by the collage material: one might argue that the novel presents gender itself a form of citation. While the central character makes herself into a woman by the advice of the women’s mags, so does every woman need this kind of “make-up” to pass as a woman. Even if her name happens to be Eve, like Roy’s demure love interest. Not giving away too much of the plot, there also seems to be a connection between trans thematics and narrative transgressions.

When you think about such larger themes, is the separation of “form” and “content” something you consider during the actual process of writing, editing or designing? Do you think with those terms?

Rawle: My first (later abandoned) version of Woman’s World was told through a series of noir-ish black and white photographs, using old dolls as the characters. I went to great lengths to get the styling right, building elaborate 3-D miniature sets: interiors, exteriors, streets, shops, vehicles and props, but after a few months, the form and content did not sit comfortably together as parts of the same idea. It became obvious that this was the wrong way to tell the story, that it would be better served using the actual text that Norma relied so heavily upon to negotiate the outside world.

Norma ‘s story, collaged on the page, becomes a physical representation of her fabricated persona. Though the text is naturally a hotch-potch of different fonts and sizes, there is an established formal grid to hold everything together and make it as easy on the reader as possible. This then allowed me, in certain dramatic moments, to break out of the grid to visually illustrate the dramatic tension of a scene. On one page, the words hover like wasps above the text column, ready to deliver a series of stinging insults; on another, a tortuous dilemma and moment of indecision on a railway bridge is underscored by the passing of a train diagonally cutting a path through the text. There is an underlying fragility to Norma’s seemingly self-assured representation of herself; I think the collaged text is a constant visual reminder of this.

Säntti: It’s also interesting that you have written a very witty novel about the perils of overinterpretation, while forcing the reader to partake in the same paranoia as the character, looking for clues and answers (The Card).

Rawle: The stories are often built on synchronistic connections. In The Card, these ‘meaningful’ patterns are ramped up to the highest level, way beyond what could acceptably be considered coincidence. I love hearing from readers who say they find themselves thinking like Riley and making similarly tenuous connections in their own lives. Riley’s on a mission; he picks up cards he finds on the street believing them to be a series of coded instructions left for him by the government. I’ve been collecting playing cards I find on the street for 25 years and they don’t appear that often—two or three a year maybe. But Riley is even more focused and obsessed than I am, so for him, they appear like magic wherever he goes. Surely, it must be a sign? What’s amazing is that I have letters from so many people who say that within a few days of reading The Card, they spot a playing card on the street, having never consciously ever seen one before.

Säntti: Likewise in Overland, your inventive use of the spread certainly has to do with surface/beneath-binarisms in more abstract and thematic ways. The novel seems to be very symmetrical in it’s overall plotting and use of binarisms.

Rawle: The suggested shape of the Overland story appealed to me straight away: I could see it had great structural potential. It enabled me to build up heaven and hell themes through parallel narratives. The story is constantly shifting between the Utopian tranquility of a fake suburban town, and the vast aircraft factory beneath it, with all its dark underworld connotations.

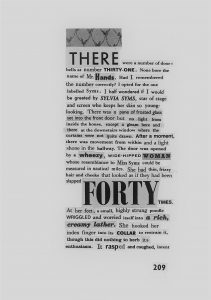

Säntti: Unsurprisingly, your novels have been discussed in literary research focusing on the experimental in literature. In her book about multimodal narration, Alison Gibbons has discussed the experiences of actual readers who encounter Woman’s World for the first time. Gibbons often proves how richly readers interpret the work, perhaps reading meanings into elements where the author remains unaware of them.[1] I suppose this is true of all writing but the merging of visual and textual make your novels especially interesting case studies. Citing your own comment in an earlier interview, she points out that as the author you may choose a word (FORTY) in capital letters and bold typeset either by chance or mostly for its look, but it is then understood to contribute significantly to narrative tone or slant, perhaps even thematics.

Rawle: Alison Gibbons comes up with some fascinating ideas and discoveries through her research. It’s interesting to find out what the reader can be encouraged to bring to the text. It is flattering and sometimes bewildering how closely analysed the book is; it has generated many brilliant academic essays and critical studies. Sometimes they reflect or clarify theories of my own; often they come up with new insights that had not occurred to me, at least on a conscious level.

I can’t let myself be too rational or analytical while I’m writing; I have to allow for the unexpected and the absurd to happen and I rely on the sense of knowing intuitively what is right.

In this case, the choice of the simple word ‘forty’ seems arbitrary, but it actually isn’t. The line is: “She had thin, frizzy hair and cheeks that looked as though they had been slapped forty times”. The word ‘forty’ may have been a chance find, initially appealing for its typographic qualities, but its addition to the sentence (along with the word ‘times’) makes the line funnier. According to Gibbons’s study of readers’ responses, by linking the visuality of the word to the narrative content of the sentence, some readers were found to attribute colour to the woman’s cheeks, not explicitly mentioned in the text. Amazing. For me, analysis and reflection generally come later. At the time, what’s important is knowing that the word ‘forty’ is better than ‘fifty’ or ‘thirty’. Why? It just is. Intuition.

Säntti: While on the subject of readers: Your series Lost Consonants, where you played with removing letters to change the meanings of (originally) rather conventional sentences and then illustrated those in surreal ways, had a long and successful history in Guardian and other papers. In England it might still be your most famous work, and it has also been used in textbooks. According to your webpage, “it has proved a surprisingly valuable teaching aid for dyslexic students.” You must be thrilled about such unpredictable uses of your work?

Rawle: Absolutely. It’s always nice when an idea or a piece of work turns out to have unexpected outcomes. The dyslexic groups particularly liked the one I did about children with leaning difficulties. (Try translating that into Finnish…)

Lost Consonants started out as a series of six, but it turned out to have greater longevity than I ever imagined. I submitted them weekly and after the sixth, as no one at The Guardian told me to stop, and I still had lots more ideas, I kept sending them in. There was no contract, no real agreement with between us, but they always printed them, and I always got paid. I sent them in for the next 15 years, nearly 800 in total.

Säntti: Your latest two novels (The Card, Overland) have a slightly more traditional look and feel than your previous work. While the idea of horizontal or landscape format is exciting, Overland reads more like a traditional novel than perhaps any of your previous work. The choice of third person narration and shifting point of view between several characters, the width of the subject matter and the backgrounding of characters all contribute to this effect.

In Overland, the unexpected setting of the text seems to add to suspense and be motivated by simultaneity and causality so the effect is not so much weird as it is immersive. There is less notable juxtaposition of the visual and the textual. I felt that this novel was easier to “read for the story” than your previous work.

Would you agree? Is this what you were going after?

Rawle: I wouldn’t say that I’m consciously moving towards creating books that are more accessible or with a more traditional feel; I think it’s just doing whatever feels right for that particular story.

With Overland, it’s true; once you’ve got used to the idea of reading the book horizontally rather than vertically, the page layout seems fairly straightforward. I think the reader quickly gets used to the notion of cross-cutting between the two narratives. The resulting blank pages add another visual clue to the spatial geography, placing the reader either ‘over’ or ‘under’ i.e. in Overland or in the factory. For me, it becomes interesting when the characters start to migrate from one world to the other, threatening the equilibrium—especially when their perception of the boundary between them becomes delusive.

Säntti: The character of Queenie, the girl looking for a break and future stardom, reminded me of many 1930’s and 1940’s working class movie heroines, especially in her way of talking. The dialogue has a very cinematic feel to it throughout. I was wondering if you made this choice to increase the credibility of the lingo? Or is there a more metafictional level?

Rawle: The first draft was actually written as a film script: dialogue and stage directions, nothing else, to be printed as a book. It didn’t quite work because I needed to get inside the character’s heads, but something of that form still remains. I wanted that cinematic feel, but I needed to show that Queenie’s Hollywood ambitions and the reality of her situation were at odds. She thinks that Overland is a film set and that she might land herself a speaking part in the movie she believes is being made. She can’t tell the difference between what’s real and what isn’t, but it turns out that none of the other residents can either.

Säntti: I have great admiration for the studio era Hollywood, so I felt right at home in Overland’s world, wincing for the poor stage-baby who has the misfortune to look like Edward G. Robinson. I loved all the little jokes about Hollywood conventions, such as Queenie describing her capability to take on stock roles for female actors: “I’m perfectly happy to be slaughtered in my home by a tribe of marauding savages, or persecuted for my political beliefs by Basil Rathbone” (176).

I get the impression that you really have a deep love for this era, not only an antiquarian’s pleasure for objects and images, but especially for the general feel of it, even for the “ugly parts” or horribly conservative aspects.

Are these guilty pleasures for you?

Rawle: They are. I’m drawn to write about the tawdry and seedy side of things, especially when seen in contrast to people’s high ideals or expectations. Typical of this are some of Norma’s scenes in Woman’s World. When she meets Mr Hands for the first time for afternoon tea in a café, she imagines the kind of picture-perfect refinement as portrayed in her beloved women’s magazines. In reality she notices that there is a piece of spat out bacon gristle in the ashtray and is confronted by a less than refined Mr Hands stuffing his face with cheap cakes and wiping his greasy fingers on the table. In a later scene Roy and Eve share a romantic picnic in a picturesque beauty spot as the sun shines down.

The sweet-sour contrast is a valuable narrative device, where one scene is made uglier or more idyllic by the other; I use it all the time, but it is never more so than in Overland. There, the Residents will be playing golf or strolling leisurely through leafy lanes, while down below in the real world, bad things happen: Queenie endures a horrific abortion, Jimmy suffers a mental breakdown and Kay is sent to a concentration camp. No wonder everyone wants to get back to Overland.

I usually write about provincial England in the 50s and 60s so Overland, set in 1942 California, was quite a departure. Apart from having to write as an American, it required a lot more research and I had to find ways to know the worlds I was writing about. Often it was through these contrasts: the Hollywood glamour of the silver screen against the backstage reality of a bit player desperate to get a break.

Säntti: In your novel, George Godfrey the designer/director has been chosen to oversee the building of Overland. He begins to see himself more and more as a god-like creator of everything around him, and finally ends up believing in his own make-believe. Overland is “as real as any other place”, he says (152).

This reminds of an anecdote about Ernst Lubitsch, the famous golden era director, who said that while he has been to Paris, France, the Paris in Paramount is the one he likes most—and also the most Parisian. Likewise for George, Overland seems to be the better reality of small town USA, the artistic reality.

This seems to be one of the themes in your novel: America itself as a product of ”visual misinformation” and especially Hollywood’s dream factory. George even comments about the similarities between movie and military industries.

Rawle: I love that quote from Lubitsch. Overland’s creator, George Godfrey, was previously an art director for MGM. He loved creating other worlds—a fishing village in Bali, a Dickensian London street or a New England country estate, but he hated it when the crew spoiled it all with their cameras, lighting booms and dolly tracks. Overland gives him to the opportunity to build the perfect town and since there is nothing there to spoil the illusion, it becomes the new reality.

In both Woman’s World and Overland, the protagonist has to fabricate a new, improved version of those ideal worlds. For Norma, her version of feminine perfection is realised in Eve. In Overland, George ultimately creates a version of heaven that is far more satisfying and spiritually uplifting than even the glitziest Hollywood ideal. There’s a joy and celebration in them, but they rely on the grubbier underpinning to make them shine.

Säntti: So while feeding our nostalgia for a bygone era in England and USA, you also seem to be implying that such a place was always an invention?

Rawle: Not so much that it’s an invention, but to acknowledge the darker side, which for me, oddly, also has a kind of perverse charm. Even Overland is susceptible to deterioration and spoiling without the care and attention of its Residents.

The domestic bliss and feminine assuredness as portrayed in 1950s women’s magazines is a fragile conceit. Did it really hold true for anyone—those single mothers working in factories and living on council estates? I suspect most of the readers of women’s weeklies were falling short of their standards. Those seeking their problem pages for advice on unwanted pregnancy, spousal abuse, mental health or homosexuality found themselves equipped instead with handy tips on the best way to polish lightbulbs or instructions on how to walk in the rain without splashing their stockings.

Säntti: Your novels often read as satirical or critical of societal norms (behavior codes, class prejudices, gender expectations). You often use the narration or point of view of outsider characters, like the character of Kay in Overland, a Japanese-American woman during the wartime. Do you recognize yourself as a political author?

Rawle: Not in that sense. I let the characters say what they would say, or make the observations they would make. I’m not necessarily looking for ways to deliver a moral or political message; it comes naturally out of the story. So Kay, finding herself in a concentration camp with all the other the American citizens of Japanese descent might question why it is that people of German of Italian heritage are not also selected for internment, which will touch on the racist motivation for the government’s decision, but I can’t make her character responsible for presenting all the historical facts or carrying the full weight of political comment about what happened. But the injustice is hard to ignore so I present the facts as part of the story’s narrative fabric and I hope that the message comes across.

Säntti: A bit like Riley in The Card, many of your novel characters have the desire to read meanings into everyday things, to look for and find patterns everywhere. They all have aspirations that might be described as quixotic. In this sense they are all artists, some only sort of.

To end this interview I just have to ask: how much of yourself do you see in these characters?

Rawle: They’re all a part of me in that they reflect aspects of my own character. They’re all quite obsessive and they’re often battling against the odds to find a better place, a better life. They don’t always get what they want, but they get what they need.

Perhaps we’re all a bit like Norma, like Riley and like George. Hopefully readers will see something of themselves in all these characters, because this is ultimately what will make them care enough to read their stories.

[1] Alison Gibbons 2012. Multimodality, Cognition and Experimental Literature. London: Routledge. See especially pages 186-187.